How sensitive is your brain to change?

This week, Martin Turnbull, an independent learning and development consultant based in Brisbane and a graduate of neuresource group’s Diploma of the Neuroscience of Leadership, looks at how the human brain responds to change and why making a change can be so difficult.

Image credit: RG Daniel

When it comes to organisational change, we like to think of change as beneficial. We strive to embrace the new way of doing business, and actively encourage colleagues and staff to do so as well. Unfortunately, many tend to reject change outright. In general, this happens because of the internal stress and anxiety triggered by uncertainty: we worry about how change might affect our comfortable, predictable world, and this makes us resistant.

Evidence from neuroscience and psychology studies reveals that our view of the world depends on a combination of the common way our brains have evolved and the growth of unique neural networks influenced by inherited traits, environmental factors, and our experiences. This unique combination gives rise to substantial behavioural differences — even among individuals from the same environment who experience the same events.

This insight is important for leaders who are embarking on organisational change. A key element in any organisational change process is communicating requirements to those who will be affected. Looking at this through a neuroscience lens, we see that, at the physical level, change messages are received by sensory inputs, passing through the central nervous system to the brain to be decoded and acted on. One of the first areas to receive sensory signals is the limbic system where the amygdala, reacting to emotional content of the decoded message, prepares our body to fight or flee by altering our biochemistry if the change is interpreted as threatening. Signals continue to spread neuron-to-neuron through the actions of hormones, bioelectric signals, and neurotransmitters to many brain areas, communicating and combining with physical and emotional responses that precede conscious thought.

This tidal wave of action passing through different parts of the brain eventually reaches the pre-frontal cortex (PFC) — the executive controller of our working memory — where it’s evaluated. Based on our internal traits and our stored memories, the PFC makes a judgement call, thus contributing to future thoughts and emotions as we transfer and project existing memories onto new thoughts to match our expectations, needs, and beliefs.

What we perceive as real includes not just a representation of the stimulus world but also that which our psyche adds to or subtracts from as it is translated into new actions and memories, all of which give rise to our unique reconstruction of the external world. However, by the time conscious thought and decision making are possible, our brain may have already settled on an initial course of action.

Unfortunately, in the case of change management strategies, this type of emotion-laden action may produce responses counter to the changes you’re hoping to enact.

Something else to consider is an individual’s innate ‘approach’ or ‘avoidance’ bias, which is due to differences within their septo-hippocampal system and PFC and may dramatically influence the acceptance of change plans. There have been numerous studies on these behaviours that attempt to explain and measure individual differences of approach or avoidance personality traits. Perhaps the most influential is a theory proposed by Jeffrey Gray describing behaviours that are thought to be governed by separate approach and avoidance systems within the brain. Gray’s theory (known as the revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST) suggests that individual differences in innate approach-avoidance traits are affected by three systems:

- The Behavioural Approach System (BAS) comprises personality traits of optimism, reward-orientation, and impulsiveness, consistent with extroversion

- The Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS) is responsible for the resolution of goal conflict through the assessment of uncertainty and risk using input from memory and the environment

- The Fight-Flight-Freeze System (FFFS) is responsible for mediating reactions to all aversive stimuli, including fear, to reduce the difference between threat and safety

If we view the relationship between innate approach-avoidance traits and an individual’s initial reaction to change, in terms of the r-RST, it’s possible an individual will react in one of four ways as depicted in Figure 1:

Figure 1

A. Those with ‘approach’ personality traits, who initially reject change, typically vocalise their dissent and openly criticise and undermine the change strategy. They do not see any reward in changing and will fight to retain the status quo. This type need convincing through messages framed with positive language to activate approach actions towards accepting change.

B. Those with avoidance traits, who initially fear change, are likely to experience levels of anxiety due to internal conflict and uncertainty that inhibits movement towards change. By playing upon this group’s innate pessimistic outlook it’s possible to create motivating messages using avoidance framed language emphasising that not changing is clearly a greater threat than the change itself.

C. Those with approach traits, who initially embrace change, actively seek and facilitate change and pose few, if any, problems for change managers. The more extroverted ones can be put to good use as ‘change evangelists’ to influence those who are undecided or not fully committed to accept change — the ‘fence sitters’ who are easier to move in the right direction than those who reject change outright.

D. Those with avoidance traits, who recognise the need for change, tend to react easily to aversive stimuli thus recognising that stagnation is a greater threat than change. This type needs reassuring throughout the process that change is still the better option. One way of doing this is to celebrate any short term wins so as to make change goals appear closer and the threat of not changing to appear further away.

The Motivation-Trait Model uses our current understanding of r-RST approach-avoidance processes to understand why certain individuals either embrace or avoid change and encourage behaviours that recognise and react to threats in appropriate ways, rather than rejecting change, being too frightened to act, or not knowing what to do.

By knowing your team well and having a clear understanding of the underlying factors at play and how each innately responds to the idea of change, you are in a better position to manage an organisational change plan. And you are also more likely to succeed.

This article is based on the paper Turnbull, M. (2015). A Model of Motivation for Facilitating Sustainable Change. Neuroleadeship Journal Volume 5, (January 2015).

Martin Turnbull is an independent learning and development consultant based in Brisbane, Australia, with an interest in the practical application of outcomes from the fields of organisational development, positive psychology, and neuroscience. Martin holds a number of qualifications, including Master of Education (Leadership & Management), Bachelor of Arts in Adult Education, Diploma and Post-Graduate Certificate in Project Management, as well as other credentials within the Australian Qualifications Framework. Martin is a graduate of the first cohort of neuresource group’s Diploma of the Neuroscience of Leadership in 2012.

Martin Turnbull is an independent learning and development consultant based in Brisbane, Australia, with an interest in the practical application of outcomes from the fields of organisational development, positive psychology, and neuroscience. Martin holds a number of qualifications, including Master of Education (Leadership & Management), Bachelor of Arts in Adult Education, Diploma and Post-Graduate Certificate in Project Management, as well as other credentials within the Australian Qualifications Framework. Martin is a graduate of the first cohort of neuresource group’s Diploma of the Neuroscience of Leadership in 2012.

How does your engagement measurement stack up?

In this post, Linda Ray, co-founder and co-director of neuresource group, shares our tools for building a high performing organisation with a sustainably engaged workforce.

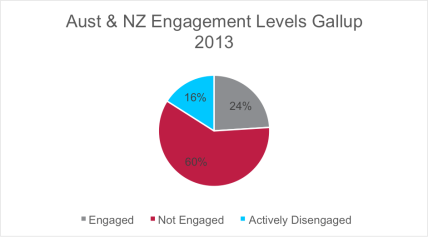

According to Gallup’s 142 country study on the State of the Global workforce only 13% of employees worldwide are engaged at work http://www.gallup.com/poll/165269/worldwide-employees-engaged-work.aspx

Whilst Australia and New Zealand are above the world average at 24% measured as engaged, there is clearly room to improve given 60% are identified as not engaged and 16% as actively disengaged.

We know that when people are not engaged they lack motivation and are less likely to invest discretionary effort. Those actively disengaged negatively impact on co-workers through emotion contagion. Many organisations measure engagement via the once per year survey and then spend a couple of months analysing the data. Clearly we need to do something differently. The reality is we used to talk about morale but engagement comes largely from inside of us and is influenced by factors outside of work. Financial stress and increasing pressures to do more with less impact on engagement. We also know that leaders influence the engagement climate as do business practices.

There are recognised keys to operating as a high performing organisation with a sustainably engaged workforce. We did a lot of thinking about this and have been influenced significantly by insights from neuroscience, particularly the ideas that the key organising principle of the brain is to minimise threat and maximise reward and the notion that the brain is a social organ.

In our work with businesses we share Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle model and consistently find that, while organisations can talk about their ‘what’ and ‘how’, rarely have they clearly articulated their ‘why’. Most organisations and businesses mistakenly believe their ‘why’ is captured by their mission statement. When your people buy the business ‘why’ and feel connected to it, they will be more motivated to put in discretionary effort. We do a lot of work with organisations to help them think through and articulate a shared ‘why’. We use a simple model in our work called the STEAR model.

In the STEAR model there are 5 key areas to pay attention to.

The first of these is to understand your strategy. Do you know your ‘why’ – why you do what you do – and are all the people in your organisation aligned to your’ why’? It is the purpose of the business and it is not about what you do but rather why you exist.

The second area is looking at the talent of your people. Have you got the right people doing the right things? We know when you can align people’s natural talents with things they like doing they will be more engaged. Do you have a development strategy for growing the capability of you staff?

Are your people consistently in a high state of engagement? Do they love what they do? Do you have practices that measure engagement regularly?

We are in a time of constant change. Times of change require us to demonstrate agility in order to prosper. How change agile are your people? What is your plan for managing change fatigue?

Finally we all need a clear roadmap. Do your people know what they have to do everyday to support your ‘why’? This links back to your purpose and your strategy. A leader/business owner needs to be mindful of all of these areas.

Focussing attention solely on the engagement, in isolation from the other key components that impact on engagement, is unlikely to change the levels of engagement.

In earlier blogs we have shared our 3 E’s model. We are using our platform Neu360 which supports a business to do quick pulse surveys to check in with their people to determine engagement ‘hotspots’. This is much more effective than the once a year survey and may mean we can intervene in a much more timely manner to address any issues that may be resulting in low morale and low engagement. What are you doing in your business to support engagement? How are you STEARing your organisation and are you paying attention to all of the areas that support a high performing organisation?

Linda is the Managing Director of NeuroCapability and the co-founder/director of neuresource group. These organisations are playing key roles in developing a new generation of thinking leaders through delivery of the Diploma of Neuroscience of Leadership and other innovative programs informed by neuroscience. Linda is gaining recognition both in Australia and internationally as a thought leader in the neuroleadership field. She is actively contributing to the body of knowledge that supports the building of individual and organisational ‘neurocapability’.

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( None so far )Are you building an intelligent enterprise?

In this post, Tara Neven, the co-founder and co-director of neuresource group, looks at why applying neuroscience to organisational leadership matters and what it means to be an intelligent organisation.

In today’s global economy and in an increasingly hyperkinetic business climate, an organisation’s long-term success is determined by the ability of its supervisors, managers or senior executives to lead effectively through periods of economic uncertainty and constant change. In an era of unprecedented complexity and disruptive change, organisations must respond quickly and creatively to shifting markets and fluctuating social, and political conditions—to survive and to thrive.

Aligning your people to your organisational strategy and having a clear roadmap for getting there, is one of the foundations of a balanced scorecard. A balanced scorecard supports you to build human capital value and an intelligent enterprise. We can’t fight biology but we can leverage what we know about it. As we understand more about how the human brain works, organisational leadership may become defined as the art of building ‘neurocapability’ and creating brain-friendly organisations.

Applying neuroscience to organisational leadership matters. Science is revolutionising our understanding of what it is to be human. An explosion of advances in human neuroscience is giving us a window into why people behave as they do and how we can manage our environments and behaviors with others to maximise results. These new scientific findings challenge old assumptions of what it means to lead. While intelligence is our greatest strategic asset, our way of life has become profoundly out of sync with our neurology, and we largely fail to practice brain-friendly leadership principles and practices.

So what is an intelligent organisation, and why should this be important to you as a business owner, director, decision maker or leader? Why should you give this focus and attention when there are so many other issues in your business to deal with (for some it is just about keeping the doors open)? Simply put, building a brain-friendly organisation addresses and manages the disconnect between what science knows and business does. Dan Pink showcased this disconnect in his 2009 Ted talk the puzzle of motivation. Fast forward five years and there is still a massive disconnect between what science knows and business does.

Our knowledge of neuroscience and its application to practical business practices and leadership is fast evolving. Some would even suggest we are living in a neuro-revolution. The question becomes: So what? How can we tap into emerging insights about the brain and apply them to the everyday work environment? How can we use what we’re learning to address the engagement and leadership crisis also regularly featured in the media?

If we embrace this new lens (through what we call the ‘neuro-lens’) to review and reinvent leadership and organisational practices and frameworks, we stand to be far more effective managers, leaders, CEOs, executives, and supervisors. The best organisations and the wisest leaders intuitively know how to create ‘brain-friendly’ environments, and they are reaping the rewards in productivity, performance, staff retention, and engagement levels.

In her article about building brain friendly organisations, Janet Crawford looks at the implications of taking brain science into the workplace. Crawford argues that many “nice to have” neuroleadership practices are, in fact, critically necessary. Organisations today use the rhetoric of work life balance, diversity and that they don’t tolerate bullying but have no real idea how to overcome it. Janet states that even if an organisation acknowledges that brain-friendly work environments are desirable, most organisations don’t truly understand how to create them, or don’t believe that they are possible.

She points out that if, as leaders, we commit ourselves to the task of cultivating environments, which optimise the human operating system, much of the rest will take care of itself. People will be excited and motivated and actually become engaged. This engagement, providing the processes are in place will last. They will think clearly and efficiently. Creativity and focus will abound. Collaboration and commitment become possible.

Neuroscience confirms something that HR and OD professionals have known for a long time: People fear change and change in the modern world is constant and is only going to get faster and more constant, change is the new norm. We need to get better at understanding change approaching change with the brain in mind.

A recent whitepaper, The Neuroscience of Leadership: Practical Applications, authored by Kimberly Schaufenbuel, program director of UNC Executive Development, examines this emerging field and provides examples of how applying neuroleadership can improve leadership practices, change management, innovation and creativity, and employee engagement.

According to Schaufenbuel, “HR professionals and leaders should try to reduce stress and anxiety by focusing on the positive aspects of the proposed change, asking questions, and listening actively to employees’ concerns. This process enhances the brain’s ability to adjust its response to the change and perceive it as non-threatening.”

If you want to get started on building your intelligent enterprise, consider these questions, can you answer or measure them?

- Do you have a clear strategic vision? – do your people know your “why” (watch Simon Sinek on TED Talks)

- Have you got the right people doing the right thing and are you supporting and developing human capital?

- Are your people consistently in a state of high engagement?

- Can your people quickly respond to unexpected challenges?

- Do your people know what they need to do every day to execute on strategy and have they got a forum to collaborate to discuss this?

Brain-friendly organisations are intelligent enterprises and they get a tick for each of these questions. They understand the importance of supporting people across the organisation to connect to the purpose or the why.

Brain-friendly organisations understand people are their greatest asset and tapping into their strengths and talents and having them doing the right job supports consistent high levels of motivation.

Brain-friendly organisations are committed to creating a workplace that engages the hearts and minds of people. Employees are not viewed as commodities with endless supplies of energy, rather they are viewed as a valuable resource.

In a climate of rapid change brain-friendly organisations have practices in place that support the organisation to be agile. Agile organisations are innovative and take advantage of unexpected opportunities as they arise. People in the business are supported to challenge the status quo and to think outside of the box.

Brain-friendly organisations understand people need a clear roadmap to implement the business strategy and support people to pursue business goals by creating strategies that keep people’s attention focussed on the areas that are important. This is key in the current environment where invitations to distract us and derail our focus are rife.

One of the best compliments I had recently from a senior leader in a large transport infrastructure company we are working with is ‘What have you done to my people? They are thinking for themselves and coming up with solutions’. Some small ‘tweaks’ to how an organisation is operating can reap big rewards. Is your organisation taking advantage of the neuro-revolution? Is it time to address any disconnects between what science is showing us and what your business does?

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( 1 so far )Collaborate Across Teams, Silos, and Even Companies

Business psychologist Rebecca Newton discusses the need for collaborative leadership and the five factors that drive success in collaboration.

_________________________

Everywhere I turn right now, I hear leaders talking about their need for collaborative leadership. It’s being identified as the fundamental differentiator in achieving strategic objectives. In order to make a difference though, it has to go beyond the polite, thoughtful behaviours of involving others, sharing information and lending strength when it’s needed. I define real collaborative leadership as: facilitating constructive interpersonal connections and activities between heterogenous groups to achieve shared goals. It is proactive and purpose-driven.

Dubai Airports offers a case study. Leaders there are being incredibly proactive in their collaborative leadership efforts, with a very clear purpose. While already running the world’s busiest airport (passenger traffic grew to almost 66.5 million in 2013, a 15% rise on the previous year), they recognised that to achieve their vision of becoming the world’s leading airport company, they need to drive a new service culture through the 3,400-person organization. But they knew they couldn’t make a meaningful change in their culture alone. To change customers’ real experience of Dubai Airports, they needed to engage their vendors and partners as well.

One of the outcomes is a customer-service training program that is being rolled out over a three-year period across many stakeholder organizations and 43,000 employees. The Dubai Airports team is investing in training for over 39,000 people outside of their own organisation, aiming to ensure behavioral consistency and therefore customer experience consistency at every possible touch point. Samya Ketait, VP for Learning and Development, says, “This is a huge project, but a worthwhile one. It means that regardless of who you meet at Dubai Airports – a police officer, a cleaner, an immigration officer… you should have the same positive customer experience. Collaborating with our stakeholder leaders has made this possible.”

While it’s spoken of highly in organisational life, it’s not something that necessarily comes easily. It may seem like a lovely, generous gesture of Dubai Airports to offer to provide customer-service training for so many other organisations’ employees, but the leaders from outside who bought into these collaborative processes had to weigh the costs of their employees’ time out of work to participate and to trust Dubai Airports with training their teams in a way that would match their own organization’s values and objectives. To sustain the three-year collaborative process and achieve its goals, these leaders recognised the behaviors that would make it work.

When it comes to collaborative leadership, these factors can drive success:

-

Focusing on interests rather than positions. As with negotiations and conflict resolution, one of the most important keys to successful collaborative leadership is focusing on interests rather than positions. When leaders are “collaborating” they are typically not from the same team – otherwise we would most likely frame it as “teamwork.” What makes teamwork different from collaboration is the goal. In collaborative leadership cases the goals may be different – the leaders may have different positions, but yet common ground can be almost always be found at the level of interests. In collaborating with others, ask: “What’s most important to you here? What really matters?”. Encourage their openness and foster trust by sharing personally what your main drivers are.

- Being an agent and a target of influence. We spend a lot of time in leadership development helping professionals to have greater influence (i.e., be a more successful agent of influence). Rightly so, as influence (e.g., influencing people towards common goals) is at the core of what constitutes leadership. Of equal importance when it comes to collaborative leadership is being prepared to be a target of others’ influence. This requires: openness to alternative ideas; inquisitiveness to understand the foundation of others’ arguments before pushing back and asserting one’s own ideas; and recognition of the value the other party has and therefore can add to the collaborative venture.

- Having clear roles and responsibilities. Research has shown that where leaders are successfully leading together, they have a clear sense of who is responsible for what. Mapping out these roles and responsibilities early, and refining them along the collaborative journey, ensures a smoother road.

- Sharing and acknowledging the credit. We know that acknowledging our own part in a problem, even if it’s taking only 5% of the blame, alleviates tension during conflict and leads to faster reconciliation. The reverse is true of facilitating collaborative success. Acknowledging others’ contributions – be they big or even incredibly small, in the success of our ventures, energizes them in our collaborative efforts. Nothing undermines collaborative leadership like one leader taking — be it actively or passively allowing others to allocate them — all the credit.

- Carving out space and time to collaborate – and a mission worthy of that effort. Too often in organisational life we know we’re meant to be collaborating and so try to squeeze it into our schedules when really we just want to get the pressing things on our to-do list done, or collaborate simply to the point of meeting our own immediate priorities. In order for collaborative leadership to be purposeful and sustainable, it needs to meet all parties’ true interests, warrant their time, and help them achieve their core objectives. Leaders need to highlight why this particular collaboration matters (not just extol “collaboration” in general), what difference it will make, and encourage the project’s participants to create the time and space it deserves.

One of the most exciting parts of the collaborative leadership journey is that while it is purpose-driven (there are clear goals and objectives in mind to achieve along the way), the end is unwritten: we never know where our collaborative leadership efforts may take us. One door opens another possibility and one creative venture prequels another.

_________________________

Article first published on the HBR Blog Network in July 2014.

.

Rebecca Newton is a business psychologist, leadership advisor, and Visiting Fellow in the Department of Management at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Is time management an outdated concept?

Linda Ray, the co-founder and co-director of neuresource group, coined the term “attentional intelligence” in 2012. In this post, she looks at how when we speak about ‘time management, what we are really talking about is ‘attention management’.

_________________________

There are a plethora of time management training programs that employees have been obliged to attend in an attempt to support them to become more efficient and ultimately more productive. The question is: do they work?

There is no doubt people walk away with a few useful tips, but do these training programs actually change employee habits around how they manage their time? From my observations and personal experience, the answer is often a resounding no. Is it, in fact, time we are managing? Or are we really managing our attention and focus in an attempt to be more productive?

The issue is really how in charge of our focus and attention we are in the increasingly hyperkinetic world we find ourselves operating within. In a recent interview, Daniel Goleman, the author of Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence, notes:

It has become an axiom of modern life that we’re a people under attack, assailed by a barrage of technologies and near-constant communications. Amidst this wealth of data and information, one resource is in short supply: our ability to pay attention.

As we learn more about human behaviour through our increasing understanding of the brain, we need to be ready to rethink some of our approaches to how we approach time management. How can we get back in charge of our attention and ultimately reclaim our time — or lack thereof?

In an article published in Global Association for Neurobiology Studies in 2009, by Lynda Klau she suggests that old solutions to time management don’t work and most traditional approaches to time management only ask us to change our behaviours, as if all our conflicts with time could be solved simply by ‘establishing our priorities’, ‘sticking to a concrete schedule’, or ‘organising our files’.

These external solutions are logical, but they’re not psychological: they ignore the internal emotional conflicts and pressures that influence us on the most fundamental levels. Klau proposes that key to improving our relationship with time is to develop a ‘mindful awareness’ of ourselves at all levels.

Students in our Diploma of Neuroscience of Leadership report noticeable improvements in their productivity through being introduced to simple concepts that support them to grow their ‘attentional intelligence’. For example:

It seems so obvious, and yet we don’t do the things each day that support us to be productive. I have been amazed at the improvements in my productivity by simply prioritising prioristing, practicing mindfulness and taking charge again of my attention. I now know how mentally taxing prioristising is and why I need to do it at the beginning of my day if I am to have any hope of getting through my ever expanding to do list. There is intense satisfaction in crossing off a greater number of items each day because I am now much more mindful of where my attention is focused and whether it is where it should be or I want it to be.

.

Replace time management strategy with a focus management strategy

Given the importance of attention and focus we recommend you develop a focus management strategy. Try out the following tips:

- Do a distraction management audit. Identify all of the external and internal distractions that vie for your attention and develop strategies to minimize them (e.g., turn off the pop-up email alert and ensure you don’t start a hard thinking task when you are hungry or thirsty).

- Chunk your day into the areas you want to focus on that will add value and schedule them into your diary. If you notice your attention moving from your plan, gently bring your attention back to where you want it to be.

- Try to remain in the present moment, if you notice your thoughts turning to past events or to the future, bring your attention back to the present moment.

- When you run out of puff, rather than pushing yourself to the limit, take a brain break. This might sound counter intuitive, however, we know the brain works best in 20-25 minute time periods before we begin looking for a different focus for our attention. Work with your natural biology as opposed to against it.

- When you experience something unexpected that leads to frustration, anger, or disappointment, notice the feeling and label it. The very act of labelling your feeling or emotion will lessen the impact and dampen down arousal in your limbic brain. The limbic brain is designed to make us pay attention to perceived threats in the environment and can easily derail our best intentions to stay focused.

- Celebrate what you have achieved in the day rather than ruminate on what you haven’t accomplished, and reset your attention plan for the next day accordingly.

Developing your attentional intelligence and becoming the CEO of your attention is key to reclaiming time. Implementing simple strategies to notice where your attention is focused and to bring it back to where you want it to be will improve your productivity and maybe even give you some extra time to do the things you enjoy.

_________________________

Linda is the Managing Director of NeuroCapability and the co-founder/director of neuresource group. These organisations are playing key roles in developing a new generation of thinking leaders through delivery of the Diploma of Neuroscience of Leadership and other innovative programs informed by neuroscience. Linda is gaining recognition both in Australia and internationally as a thought leader in the neuroleadership field. She is actively contributing to the body of knowledge that supports the building of individual and organisational ‘neurocapability’.

Linda is the Managing Director of NeuroCapability and the co-founder/director of neuresource group. These organisations are playing key roles in developing a new generation of thinking leaders through delivery of the Diploma of Neuroscience of Leadership and other innovative programs informed by neuroscience. Linda is gaining recognition both in Australia and internationally as a thought leader in the neuroleadership field. She is actively contributing to the body of knowledge that supports the building of individual and organisational ‘neurocapability’.

.

.

5 things you can do to as a leader to make your organisation more productive

Adair Jones, a Brainwaves for Leaders staff writer, looks at how applying neuroscience to work practices can make organisations more productive.

_____________________________________________

Most organisations are committed to keeping apace of technological advances, updating equipment frequently, and devoting resources to state-of-the-art processes and materials. The general feeling is that constant upgrades are a necessity to survive in an increasingly harsh and competitive economic climate. It’s perplexing, however, that this attitude doesn’t extend to any organisation’s most important resource – its people. Dated thinking, old-school beliefs, and outmoded approaches are all-to-often applied to how people work together. And leaders are left wondering why productivity falters. Outdated management thinking insists the psychology is not relevant to business. However, what we are discovering about the brain tells us that this just isn’t the case. We now have scientific evidence that what goes on inside the brain, from emotional responses to higher cognitive skills, impacts everything we do and should be incorporated into how we structure work. Brain functions affect perception, emotion, and conscious thought. More and more, leaders are borrowing from neuroscience research, and we are beginning to see practical applications – and big rewards – in the workplace.

The top five ways to use what we’re learning from neuroscience to improve productivity

Manage expectations Because motivation plays a critical role in how and why people function the way they do, it’s important to understand that the brain is essentially a social organ. Research clearly shows that the brain’s primary organizing principle is to detect whether incoming stimuli is a reward or a threat. It’s part of our early survival mechanism that allows the brain to quickly classify the “danger” level of any situation. Understanding this, it’s possible to manage expectations of employees and clients alike. Because no two brains are alike, this can be complicated, but it’s well worth the effort to learn what motivates each person and to what degree. Wolfram Schultz of Cambridge University in England has studied the links between dopamine and the brain’s reward circuitry. When a cue from the environment indicates you’re going to get a reward, dopamine is released. Interestingly, unexpected rewards release more dopamine than expected ones. This means that the surprise success, like unexpected praise, for example, can positively impact your brain chemistry far more dramatically than an expected promotion or pay rise. On the other hand, if you’re expecting a reward and don’t get it, dopamine levels fall steadily. It could take some time for a person to internalise this disappointment, re-frame it, and regain lost momentum at work. The savvy leader anticipates where expectations might be overshooting the mark and works to minimise them as much as possible. Keeping expectations low avoids disappointment if a goal isn’t achieved and sets up a situation for happy surprise and delight if it is. Understand emotions Remember, emotions are contagious. The moods of others, especially those in positions of power, can have a real and lasting effect on individuals and groups. Toxic bosses, bullying environments and aggressive cultures can infect every one. Leaders play an important role in their ability to influence the spread of certain types of emotions over others. Your emotions matter because they impact on those around you. A growing body of evidence emerging from the social cognitive neuroscience field suggests that many of our emotion regulation strategies not only don’t work but are bad for our health and those around us. Matthew Lieberman, of UCLA, found that learning to label our emotions maximises cognitive ability. He’s found that using simple language to ‘name’ anticipated and experienced emotions, actually lowers the arousal of the limbic system producing a quieter brain state. This in turn, allows the prefrontal cortex – the brain’s CEO – to function more effectively. Suppressing emotion is the most commonly used emotion regulation strategy. Studies show that suppressing emotion physiologically impacts on those around you and increases heart rate and blood pressure of those you are interacting with. The discovery of mirror neurons has also shown how we are wired to detect and mirror emotion of others. The brain is highly tuned to emotions in others, which can in turn generate reward or threat cues. Many studies examining the emotion contagion effect are showing their impact on morale in an organisation. Fear, anxiety and anger are contagious but remember so is enthusiasm and joy. Develop attentional intelligence Attentional intelligence allows you to effortlessly but ‘mindfully’ notice where your attention is at any moment and to intentionally choose where you want it to be. This kind of mindfulness can have a huge impact on productivity. In a study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, conducted by Zindel Segal and colleagues, mindfulness meditation has been found to be as effective as antidepressants to prevent depression relapse. If it’s that powerful for people overwhelmed with troubles, imagine what it can do for those who are healthy and motivated. Greater focus, more effective planning, and greater stress reduction are just a few of the benefits. If we operate in the present, rather than brooding about the past or feeling anxious about the future, our minds are clear to deal with the issues at hand. It’s a simple principle, really: what we pay attention to gets accomplished. What we think, what we do, and what we focus on actually changes the structure and function of our brains. But, like any training, it takes practice for this to take full effect. It ultimately enables you not only to become calmer but also more creative. Cultivate creativity  A number of large surveys done in the past few years show creativity at the top of the business leader’s wish list. It’s instructive to know then, what creativity needs to thrive. Old notions still prevail about creative types – that like leaders, creatives are born, not made. This just isn’t the case. We are all creative. In fact, it’s one of the defining characteristics of being human. However, creativity does require cultivation. Different parts of the brain and different areas of focus yield different results. For example, holding big picture ideas and day-to-day details in your mind at the same time can lead to major stress. This common problem was first identified by J.P. Guilford in 1967 as two different types of thinking that occur in response to a problem: divergent thinking generates ideas, while convergent thinking sorts and analyses these ideas towards the best outcome. This concept explains why we find it so difficult to come up with a snappy title that completely illustrates everything in that detailed power point presentation you’ve just written. Respect your limitations Respecting our limits isn’t something modern Western culture encourages us to do. We are taught to break down barriers, reach for the stars, and never-say-never. However, acknowledging that you are tired or burned out or unmotivated can be incredibly liberating and ultimately restorative. As long as you take positive action to rest, relax, and nourish yourself. As long as we are grounded in our human bodies, there are basic needs and limits that warrant respect. Eat when hungry, rest when tired, say no when too busy. Attitudes towards sleep also plays a role against ‘nurturing’ the seeds of creativity and productivity. Yes, sleep! Getting a good night’s sleep on a regular basis can do wonders for productivity. When our alertness dips mid-afternoon, as it’s genetically programmed to do even when you are well-slept, responding with a powernap is a proven way to boost mood, concentration, alertness and memory. An awareness of how advances in neuroscience might best be applied to the workplace can bring about amazing results in performance and productivity. The best news of all is that it doesn’t take a big organisational overhaul. Incorporating small shifts in thinking and doing yield big results.

A number of large surveys done in the past few years show creativity at the top of the business leader’s wish list. It’s instructive to know then, what creativity needs to thrive. Old notions still prevail about creative types – that like leaders, creatives are born, not made. This just isn’t the case. We are all creative. In fact, it’s one of the defining characteristics of being human. However, creativity does require cultivation. Different parts of the brain and different areas of focus yield different results. For example, holding big picture ideas and day-to-day details in your mind at the same time can lead to major stress. This common problem was first identified by J.P. Guilford in 1967 as two different types of thinking that occur in response to a problem: divergent thinking generates ideas, while convergent thinking sorts and analyses these ideas towards the best outcome. This concept explains why we find it so difficult to come up with a snappy title that completely illustrates everything in that detailed power point presentation you’ve just written. Respect your limitations Respecting our limits isn’t something modern Western culture encourages us to do. We are taught to break down barriers, reach for the stars, and never-say-never. However, acknowledging that you are tired or burned out or unmotivated can be incredibly liberating and ultimately restorative. As long as you take positive action to rest, relax, and nourish yourself. As long as we are grounded in our human bodies, there are basic needs and limits that warrant respect. Eat when hungry, rest when tired, say no when too busy. Attitudes towards sleep also plays a role against ‘nurturing’ the seeds of creativity and productivity. Yes, sleep! Getting a good night’s sleep on a regular basis can do wonders for productivity. When our alertness dips mid-afternoon, as it’s genetically programmed to do even when you are well-slept, responding with a powernap is a proven way to boost mood, concentration, alertness and memory. An awareness of how advances in neuroscience might best be applied to the workplace can bring about amazing results in performance and productivity. The best news of all is that it doesn’t take a big organisational overhaul. Incorporating small shifts in thinking and doing yield big results.

_____________________________________________

. Adair Jones is a writing and communications expert with over 20 years experience. She contributes regularly to newspapers, magazines and online journals and has won awards for her fiction. Writing about developments in neuroscience is her latest passion. . . .

. Adair Jones is a writing and communications expert with over 20 years experience. She contributes regularly to newspapers, magazines and online journals and has won awards for her fiction. Writing about developments in neuroscience is her latest passion. . . .

This is your brain on long meetings…

Linda Ray, the co-founder and co-director of neuresource group, coined the term “attentional intelligence” in 2012. In this post, she looks at the reasons long meetings get in the way of productivity and what can be done about it.

_________________________

On a good day, you wake up rested and raring to go. You make a mental list of things to do during your commute and, by the time you walk through the door of the office, you are clear about what needs to get accomplished and in what order. There’s only one problem: the early morning meeting that usually runs overtime. Your mood deflates and your momentum screeches to a halt. Not only that, you may not regain momentum for some time after the meeting has ended – if you regain it all all.

Your brain on long meetings

The brain is easily exhausted. Our brains frequently shift its focus between external events and internal memories and interests. It’s designed this way in order to consolidate learning and long-term memory. However, every time you focus your attention you use a measurable amount of glucose and other metablic resources. This makes attention a limited resource. Long meetings have the effect of exhausting cognitive reserves. Focus decreases as the meeting drags on. Unfortunately, the brain requires regular replenishment to retain attention and to remain engaged.

Crammed agendas are overwhelming. When faced with a daunting agenda, the default is for people to look at their watches. Attention is on the time rather than on the discussion at hand. Eyes glaze over. People stop listening, begin to doodle, think of the weekend. All of this hampers productivity.

The brain wants assignments that are achievable. Too often, meetings are used as a way of generating ideas rather than actions. But the brain wants certainty and is always looking for the reward of breaking down tasks into manageable chunks – a to-do list that can be completed to a schedule and in good order.

Emotions are contagious. The recent discovery of mirror neurones explains the phenomenon we’ve all experienced: when one person begins to yawn, people nearby begin yawning too. All it takes is one sleepy or fidgety person in a meeting to affect everyone around the table.

Efficiency can hinder productivity. When brains come together, they can accomplish great things – but trying to silo a group’s efforts into agenda chunks isn’t the best way to realise that greatness. People need time to coalesce around an idea, to work it like clay, and to test different ways of making it happen.

Focusing on numbers saps creativity. If everyone believes that the real reason for the meeting is to figure out how to ‘make the numbers’, creativity is sapped before the meeting even begins. Structuring meetings around financial performance metrics is not a good way to motivate people. Ideas are motivating. Developing and nurturing ideas will ultimately lead to making the numbers. Sadly, conventional meetings almost always have this backwards.

Meeting to prepare for the next meeting is not rewarding. Since our brains are reward-driven organs, knowing that the follow-on reward for spending all this time in a meeting is simply to have another meeting is not at all motivating.

7 things you can do about it

Implement a block on early meetings. Take the first hour of the day and throw it out the window – for meetings, at least. By refusing early meetings, you can spend time prioritising your to-do lists, including prioritising which meetings are actually necessary. You might be amazed at how much you can accomplish when you free your mornings for planning.

Implement a block on early meetings. Take the first hour of the day and throw it out the window – for meetings, at least. By refusing early meetings, you can spend time prioritising your to-do lists, including prioritising which meetings are actually necessary. You might be amazed at how much you can accomplish when you free your mornings for planning.

Take breaks. Focusing for an hour to an hour and a half can be exhausting for our brains. Our brains gets depleted, start making errors, and we may grow irritable – not the best formula for planning and making decisions. Short breaks, even if they’re only a couple minutes, offer some much needed rejuvenation.

There’s a catch to making those breaks effective, however. Don’t use break time to email your boss or sign off on a report or discuss team goals with a colleague. To help your brain recover from absorbing an hour of PowerPoint slides, try to forget about work during your break.

Look for novelty. If you find yourself bored in a meeting, try – really try – to find something interesting going on in the room. You can train your brain to look for novelty in what’s happening around you, something that both lengthens your attention span and gives you better control over it. Look at the people around the table and try to imagine something interesting and positive about them.

Remember the purpose of the meeting. As you fixate on details, wade through different viewpoints and perhaps lament over that to-do list, it may be easy to forget the point of the meeting. Think back to the meaning of the meeting, and ask, ‘Why are we doing this?’. Whenever you find your attention is wavering, remember why you’re there. Write it down in your notepad. By examining the cause of the meeting, you may find yourself “considering it a privilege rather than a duty.”

Go back to the basics. Engage in the meeting, whether it’s asking questions, proposing ideas, or at the very least, taking notes. It’s also a good idea to leave phones at desks in in handbags in order to avoid distraction. Bouncing back from a single distraction can take several minutes. It’s also useful to practice active listening skills.

Snack and hydrate. Bring water to meetings and snack wisely beforehand. Say no to high-carbohydrate, high-energy density foods that will tempt you to rest your eyes (just for a second!) a few minutes into the meeting. Opt instead for healthy fruits, vegetables, and trail mix.

Make them shorter and more frequent. Incorporate daily or twice weekly 10-minute standing meetings into your workplace. Ideally, the 10-minute standing meeting has an agenda of no more than four items. This works nicely with our brains preference for chunking information. Also, the fact that people are standing rather than sitting helps. Your blood circulation increases. Standing is also mentally revitalising, making you sharper and more aware. What seems like an insurmountable pile of paperwork when you’re sitting down appears suddenly manageable while standing. Standing can even improve motivation, morale, and mood.

_________________________

Linda is the Managing Director of NeuroCapability and the co-founder/director of neuresource group. These organisations are playing key roles in developing a new generation of thinking leaders through delivery of the Diploma of Neuroscience of Leadership and other innovative programs informed by neuroscience. Linda is gaining recognition both in Australia and internationally as a thought leader in the neuroleadership field. She is actively contributing to the body of knowledge that supports the building of individual and organisational ‘neurocapability’

Linda is the Managing Director of NeuroCapability and the co-founder/director of neuresource group. These organisations are playing key roles in developing a new generation of thinking leaders through delivery of the Diploma of Neuroscience of Leadership and other innovative programs informed by neuroscience. Linda is gaining recognition both in Australia and internationally as a thought leader in the neuroleadership field. She is actively contributing to the body of knowledge that supports the building of individual and organisational ‘neurocapability’

.

.

.

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( 3 so far )

Disconnect: what science knows versus what business does

On the weekend of June 14-15, 2014, Linda Ray and Tara Neven, co-founders and co-directors of neuresource group, headed down to Jupiters Hotel & Casino on the Gold Coast for the National Retailers Association (NRA) Conference. Both had important roles to fill – Neven as the conference host and Ray as an ‘Insight’ speaker.

The summit was the first of its kind for the National Retailers Association with a specific focus on “people and operations development” (also known as POD). The POD concept provides a unique platform for applying groundbreaking ideas to the world of retail – and, for that matter, event management.

Neven said. “I’ve been very impressed with how acute and far-sighted the organisers have been to include some of our ideas in order to make the summit more brain-friendly. This includes offering brain-friendly food, delivering content in ‘chunks’, and giving practical applications as to how neuroscience can change the way people work.”

Ray’s keynote address focused on the disconnect between what science knows and what business does. For example, in order for people to remain productive, people need to be kept in a ‘reward’ state. This isn’t necessarily about money or accolades, rather, it refers to how the brain is organised. At any given moment, we can be either calm and engaged, moving towards an experience, or we can feel threatened and want to move away from an experience – in other words, so stressed we feel pushed into a fight or flight state. The problem is that many workplaces are set up in such a way that people are kept uncertain, worried about status, with little autonomy. A command-and-control hierarchy actually prevents people from being productive.

Science tells us that we can do only one thing at a time, and yet more and more demands are heaped on our heads. We are asked to do more with less support. Time is fractured by long meetings and constant interruptions. Multitasking is a myth and yet many businesses require their employees to switch tasks all day long. Not only does this tire the brain, leading to increasing ineffectiveness, but it can take up to 23 minutes to get back into the thinking space you were in before the interruption.

“It’s a wonder we get anything done at all,” Ray says.

She has a solution, however. Science has shown that adjusting one’s attention can have a big impact on focus. Being aware of your awareness builds ‘attentional intelligence’, a term Ray coined in 2012. She defines attentional Intelligence is an intelligence which when highly developed allows you to effortlessly but ‘mindfully’ notice where your attention is at any moment and to intentionally choose where you want it to be.

“The problem is,” Ray adds, “most workplaces are hives of distraction. We need to find ways to offer quiet spaces for long stretches of time, as well as open areas for meetings and social connections.”

The brain-friendly organisation accommodates all kinds of work tasks and all types of work preferences.

We know from science that the brain resists change. However, many businesses are constantly seeking new ways of doing things, often implementing change plans without considering that employees feel stressed when changes are announced and they are naturally designed to revert to old ways of doing things when they feel stress. Handled the wrong way – by not considering the neuroscience of change, in other words – means a change plan is set for failure even before it’s been implemented.

“The paradox is that the brain is highly plastic throughout our lives, so we know we can change. We just have to get the formula right, Ray says.

It can take anywhere from 18 – 236 days for a planned change to become a habit. It is no wonder, then, that a big issue facing organisations attempting to implement a change plan is that change doesn’t always happen to the proposed schedule and it doesn’t always ‘stick’. Even when employees are well-prepared and amenable, it’s still important to communicate openly (avoiding threat states), focus on areas of resistance (developing emotional intelligence), and remain patient. In time, brains can be rewired to accept new processes and procedures in ways that are sustainable over the long-term.

Ray left the audience with a final question: “What can you do when you get back to work to address the disconnect between what science knows and what your business does?”

She suggests it might be time to do something different.

“All of the speakers offered solid insights and emphasised that engagement, vulnerability, and a focus on increasing the number of women in senior leadership were the way forward,” adds Neven. “And we think the best way to do this is to use what we’re learning from neuroscience in our business practices.”

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( 3 so far )

« Previous Entries